How we got here

Few presidents have made truly consequential contributions to mental health in America – and it shows

The president of the United States often sends a signal about their priorities early in their administration. We talk a lot about “day one” actions or what the president will do in their first 100 days. And each time a new president comes into office, there’s renewed hope that maybe this president will take on [insert your issue here].

So, what have our presidents done on mental health? This is my issue, the area that I think needs more action, and the one topic I just so happen to think has not gotten the appropriate amount of attention considering how it impacts everyone.

In this week’s missive, I briefly summarize some of the presidential actions taken toward mental health over the years, with a specific eye on their decisions and how they have positioned us where we are today. After all, to effectively fix the present, we need to first understand the past.

1963 is as good a place as any to start, because even though President Harry Truman passed the National Mental Health Act in 1946 – which established the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and began to put government resources towards mental health research – President John F. Kennedy gets most of the credit for policy and mental health reform by having signed the Community Mental Health Centers Construction Act that year.

The Community Mental Health Centers Construction Act called for previously institutionalized individuals to be returned to their communities and receive treatment from those local centers if it were safe enough for them to do so. He did this because evidence was – and remains – that improvement was more likely to occur inside communities defined by hope, healing, and upward mobility than faraway institutions formerly referred to as asylums.

President Kennedy had the right idea: Get people into the community, surround them with support and give them a chance to succeed. This groundwork policy, which put $3 billion into building a national network of community mental health centers meant that state psychiatric hospitals began to empty their beds immediately. And in principle, this was the right thing to do - the problem, amongst many others, was that the system was never truly built and he didn’t get to personally see those changes through. The Act was signed Oct. 31, 1963 and President Kennedy was assassinated less than one month later – and his successor just didn’t have the resources necessary to make this vision a reality. The lack of financial investment and overall implementation of this Act still haunt us to this day.

Many of Kennedy’s policy ideas, which were based on the best thinking and available evidence at the time, were codified into policy and regulation when President Lyndon B. Johnson signed legislation that established the Medicare and Medicaid programs in 1965. But even despite President Johnson expanding funding for mental health via the Mental Health Amendments of 1967, there was still a patchwork quilt of funding mechanisms that never satiated a starving mental health system by the end of his term. Little did we know that this would just be the beginning of a series of decisions that would only further fragment mental health from the rest of health care.

Progress largely stalled until the next Democratic president, President Jimmy Carter, came into office. After it became immediately apparent that our nation’s communities were not prepared to support individuals with varying degrees of mental health needs, President Carter saw mental health in America as the crisis that it was and responded. Mrs. Rosalynn Carter, the first lady, was also a staunch advocate for mental health reform – and to this day still is helping lead major mental health reform from The Carter Center in Atlanta, Georgia.

In 1977, President Carter signed E.O. 11973, effectively establishing the first-ever President’s Commission on Mental Health. Twenty experts in medicine and mental health care, administration, and consumer rights served on that committee, working together to create and manage task panels whose mission was to help evaluate mental health access and affordability for various populations across the United States. The results of the commission’s findings were published in a four-volume report with recommended actions that are still relevant today (a running theme for many such reports and committee recommendations). For example, we still need to “develop networks of high quality, comprehensive mental health services throughout the country… ” that are rooted in local communities, and “assure that appropriately trained mental health personnel will be available when they are needed.”

Having completed its primary task, the committee was relieved of its duties with E.O. 12110, which was followed shortly thereafter by the signing of the Mental Health Systems Act in 1980. The Mental Health Systems Act, presented by Senator Edward Kennedy, sought to act on some of the recommendations contained in the commission’s report by providing grants to community mental health centers, but it wasn’t given the time it needed to produce its desired results. President Ronald Reagan repealed much of the Act in 1981, which pushed a great deal of the responsibility for mental health back to the states. This decision in part is why Medicaid plays such a critical role for addressing mental health and addiction even today as the largest payer for these services.

More than twenty years passed before President George W. Bush signed E.O. 13263 in April 2003, creating another presidential mental health commission called the President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. This commission, similar to that created by President Carter’s E.O., made a series of recommendations around reform, many of which were grounded in the concept of recovery. The commission’s report specifically noted a major problem with any and all mental health reforms which is that the dominant funding mechanism for mental health, the Mental Health Block Grant, does not adequately provide enough funding to scale many mainstream programs. (This is a common thread between all of the policy initiatives mentioned here and was a part of the 1981 Reagan legislation.)

Major improvements to mental health were made under the Bush and Obama administrations just a few years later – but mainly in the health insurance domain and did not fix some of these larger structural flaws.

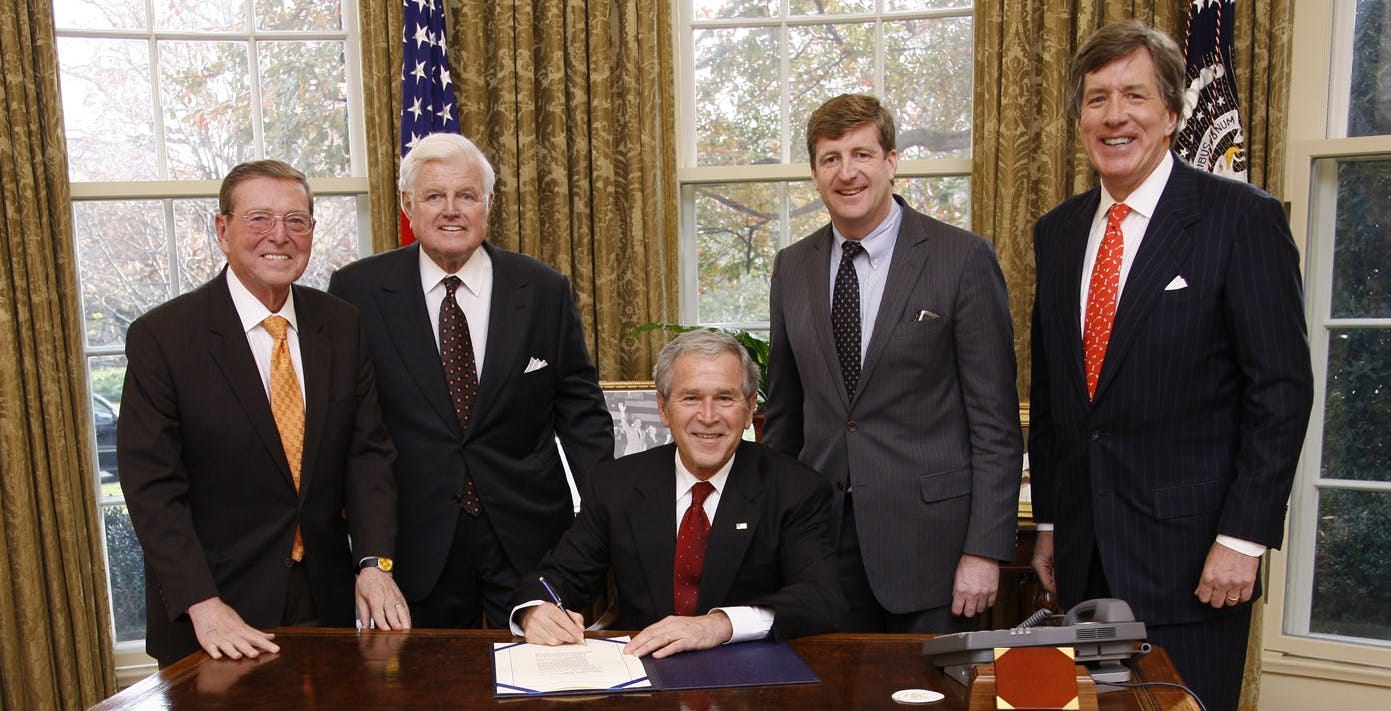

The first improvement under President George W. Bush was through the signing of the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) in 2008, which made it a violation of federal law for health insurance plans to not cover mental health or substance use disorder (MH/SUD) care as they would other kinds of patient care e.g. medical/surgical benefits. As a reminder, mental health benefits were not really a reliable health insurance option before 1961. President Kennedy tried valiantly to require the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program (FEHBP) to cover mental health benefits at the same level as medical benefits, but this was a fight that went on for years. To an extent, it still is, as the MHPAEA – which notably another Kennedy, Congressman Patrick Kennedy, helped author – remains in place, but largely unenforced.

The second major improvement was during the Obama administration and can be found in a little known law called the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA). The ACA provides some of the best mental health and addiction insurance provisions this nation has ever seen building off the 2008 MHPAEA legislation. Specifically, the Affordable Care Act:

● Prevents insurance companies from instituting lifetime limits on behavioral health care, allowing individuals seeking treatment for mental health issues or substance abuse to do so for as long as is medically necessary.

● Keeps insurance plans from being able to refuse coverage for individuals with preexisting conditions – which include depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, PTSD and schizophrenia.

● Defines addiction, mental and behavioral health services as essential health benefits, meaning all insurance plans are obligated to cover care options such as psychotherapy and counseling, inpatient services and substance abuse treatment.

● Requires that certain preventive services also be covered by all insurance plans at no cost, including depression screening for adults and behavioral health assessments for children.

● Gives states the ability to increase the number of people eligible to enroll in Medicaid, which remains the largest payer for mental health and addiction services.

And of course, along the way in our nation’s history we had some great leadership from Surgeon Generals on mental health, but that’s an entirely separate post.

Like I said at the beginning, when a new president enters office, we have a renewed sense of hope that they will finally address the causes we care most about. Now, in 2021, we have another president in office, a president who has demonstrated an understanding of the severity of America’s mental health crisis, and a familiarity with some of the solutions the nation’s people so desperately need.

So, what will we see next? We have a bipartisan issue that seems to transcend politics. We have a national crisis where everyone’s mental health is put front and center because of the deadly COVID-19 pandemic. It seems like a time for us to see some bold action, courage, leadership, and a profound understanding of where our fragmentation began, plus what it will take to finally end it – things that will be referenced decades later like President Kennedy’s work still is today.

We can’t know for certain whether President Joe Biden will rise to this challenge. But what we can do is be prepared with actionable strategies, a vision, and a plan to work together to increase our local and federal leaders’ awareness of the solutions we need right now – solutions you can rest assured I’ll be sharing in future posts.