Why is it so hard to put better mental health policies in place? Part III

A continued look at what it takes to make mental health reform a reality

Last week, President Joe Biden signed into law the American Rescue Plan, a $1.9 trillion Covid-19 relief bill that dedicates nearly $4 billion to mental health and addiction services.

Here is just a highlight of a few areas where some of that funding is going:

· Sec. 2701 $1.5 billion for the community mental health block grant

· Sec. 2702 $1.5 billion for the Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment block grant

· Sec. 2703 $80 million for mental health training for health care professionals, paraprofessionals and public safety officers (evidence-informed strategies for reducing and addressing suicide, burnout, and mental and behavioral health conditions

· Sec. 2704 $20 million for CDC Education and awareness campaign encouraging primary prevention of mental health conditions and help-seeking for mental health concerns, identifying risk factors in self and others

· Sec. 2705 $40 million for HRSA to issue grants to FQHC’s and provider associations or health care entities for programs or protocols to promote mental health among providers, staff, and members

· Sec. 2706 $30 million for overdose and harm reduction services

Add these to the White House Senior Advisor for COVID Response, Andy Slavitt’s, other callouts, and he’s absolutely right:

It’s “a BFD” because it’s hard to get any funding, let alone four billion dollars’ worth, committed to mental health and addiction these days. Stigma, shame and misconceptions – as Meghan Markle highlighted last week with her announcement about being denied access to mental health care for the sake of what that might look like for the institution – has kept mental health and the policies to improve it largely stuck on the sidelines.

Also, as we already discussed, it’s not uncommon in committee work for mental health legislation to be set aside and die, or delayed long enough that it expires with the end of a legislative session. Let’s unpack that a little more and get back into what it takes to make policy.

SO, WHAT’S A LEGISLATIVE SESSION?

A legislative session is a period of time in which representatives and senators come together to introduce, discuss and approve bills. Congress has an annual session starting in early January (usually Jan. 3) and usually ending in December of that same year, or early January the year after (again, usually Jan. 3). Most states have a similar annual schedule, with the exception of four that meet only during odd number years – something that proved to be a real pain for Nevada, Montana, North Dakota, and Texas when they were forced to come up with a COVID response plan last year.

To be clear though, even if legislators meet each year, that doesn’t necessarily mean that they meet every single day of that year. Congress breaks in August – a tradition that dates back decades – and also recesses other parts of the year too. See here for a sampling of when those other recesses tend to be at the federal level.

Those break periods actually give birth to other kinds of sessions. A regular or daily session is one in which lawmakers conduct the business I’ve laid out in my late few posts. (Start here if you’re just joining us.) But there can also be an extraordinary session called by a governor at the state level or the president at the federal level; a joint session where both the House or state Assembly and the Senate come together; a lame duck session after an election, during which time outgoing legislators must still participate in the policymaking process; and more.

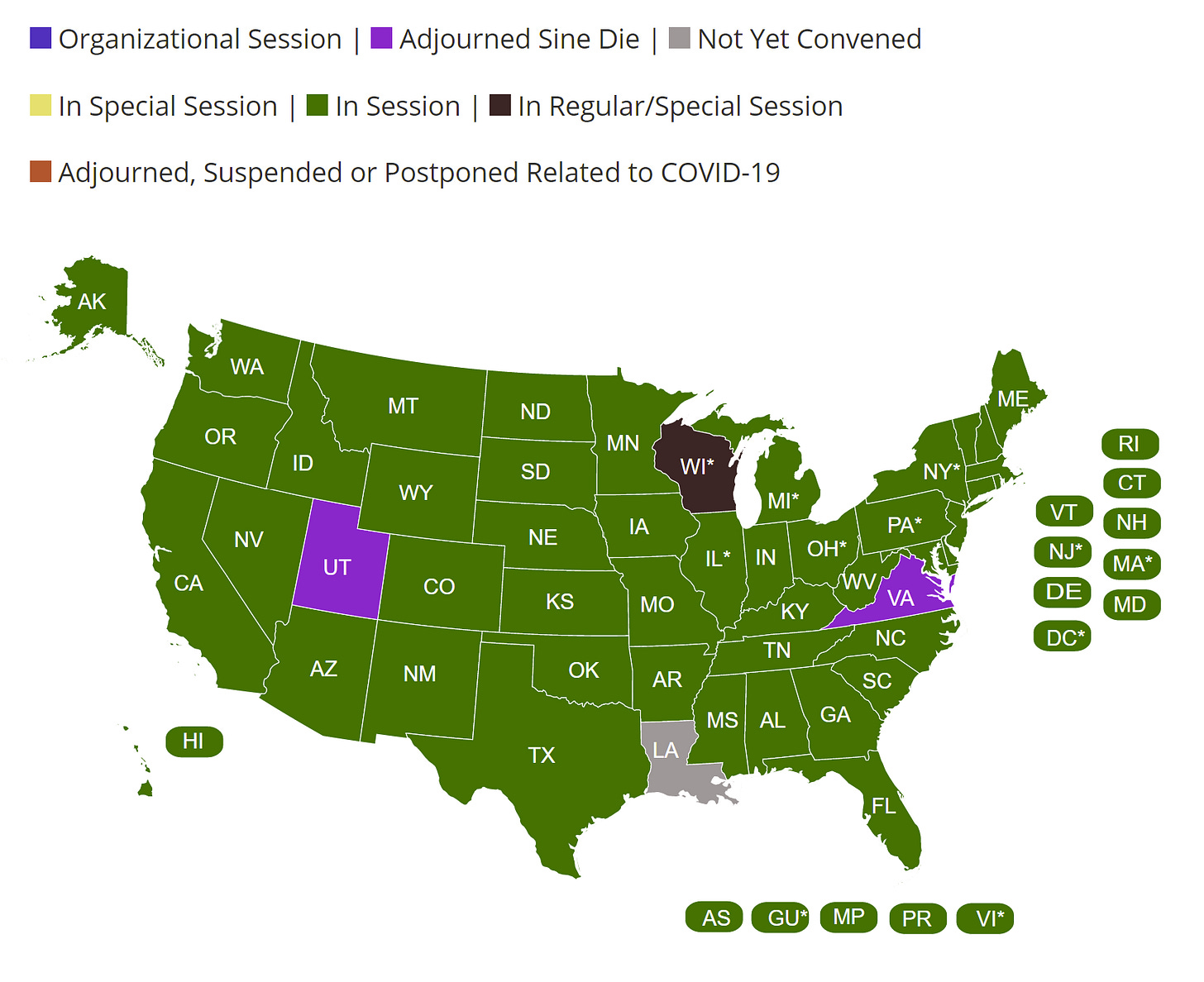

The National Conference of State Legislatures has a map showing the session status of each state, and CQ Roll Call Congress’ 2021 calendar.

WHY DO I NEED TO KNOW ABOUT SESSIONS?

Like I said before, timing is everything. You can have the best, most beautiful and impactful bill, but if it’s presented at the wrong time, it could be destined for failure. For example, if you are trying to present a bill addressing an urgent need in your state at a time when your state legislature isn’t in session, by the time your state legislature is in session, your bill could be irrelevant, less impactful, and less likely to pass. If this is the case – or if no state legislators take your issue on – consider reaching out to a member of the U.S. House of Representatives representing your state, or a Senator.

Timing matters at the federal level as well. Consider what happened with H.R. 1109, the “Mental Health Services for Students Act of 2020.” This bill seeking to bolster school-based mental health services was introduced to the U.S. House of Representatives back in February 2019, was promptly assigned to the House Committee on Energy and Commerce, then the subcommittee on Health, and didn’t have a hearing until over a year later in June 2020. After mark-up, it was reported out in September 2020 and sent to the Senate, where it died because it wasn’t passed before the conclusion of the 116th Congress on January 3, 2021.

The good news is that Rep. Grace F. Napolitano reintroduced the bill as H.R. 721, "Mental Health Services for Students Act of 2021," last month. But even if both the U.S. House and the U.S. Senate would have passed H.R. 1109 and sent it to the president, it still wouldn’t have been immune to timing. Once the U.S. House and U.S. Senate pass a bill, with the exception of Sunday, the president has ten days to sign it into law. If the president vetoes a bill during that time frame, that veto can be overturned by a two-thirds vote of Congress. But if the Congress adjourns during that ten-day period, meaning that the President can’t return the bill to Congress and give them the chance to override his decision, the president can veto a bill by way of what’s called a “pocket veto.”

WHAT CAN PUSH A POLICYMAKER TO VOTE YAE OR NAY?

As I wrote earlier, there are decisions that “can be motivated by personal political ideologies,” and there are decisions that can be influenced by special interest groups. Special interest groups are just that, groups of people with a shared, special interest that they want to either protect or promote through lobbying – which, in action, looks like making phone calls, writing letters, and creating campaigns that will hopefully sway legislation and public opinion in their interests’ favor.

Especially among policymakers who are unfamiliar with the innerworkings of a particular issue that a bill aims to address, lobbying can have a huge influence. And when it comes to mental health, the interest groups that have a tendency to get in the way of those policies being put in place are those backed by the people who are at risk of losing the most. For mental health, these people are sometimes those in the health insurance industry or provider organizations – and yes, sometimes even hospitals. Why, though usually not marketed as such, has everything to do with what we started this post talking about: money. Mental health parity, which would put mental health care on par with physical health care, would mean that health insurers have to fork out more moolah, that providers potentially lose patients to other providers, and that hospitals potentially be forced to take on something that they don’t see as benefiting their bottom line.

As a mentor of mine once said, health care is a morass of competing business interests, and in no place is that seen more than when health care is on the docket for policy reform.

Just how much influence have the interest groups representing these organizations had on our elected officials? See for yourself in my next post – the numbers don’t lie.