Where we are now – in the words of Homer Simpson

How COVID-19, shrinking budgets, and worsening mental health make the current moment a "crisitunity” to overhaul our nation’s mental health system

Leave it to the Simpsons to give us the right word for the moment.

Lisa Simpson was only partly right by saying to her dad, Homer, that the Mandarin words for “crisis” and “opportunity” are the same. To be clear, 机会 is opportunity and 危机 is crisis – they share a similar word but are different definitions from one another. The Mandarin word for “crisis” is a combination of two characters whose meanings are often misinterpreted as danger + opportunity. Linguistic scholars can tell you all the problems with this – if you want that linguistic rabbit hole, be forewarned and click here – but that’s an entirely separate topic for another author on another blog. My point here is that after decades of scattered and often disjointed presidential actions to improve mental health, right now, our nation is in the middle of a crisis AND an opportunity.

THE CRISIS

The numbers don’t lie. Kaiser Family Foundation has been tracking adults reporting depression or anxiety symptoms since the early days of the pandemic in April 2020, and as you can see in the following graph, about one-third of the country reports experiencing these symptoms.

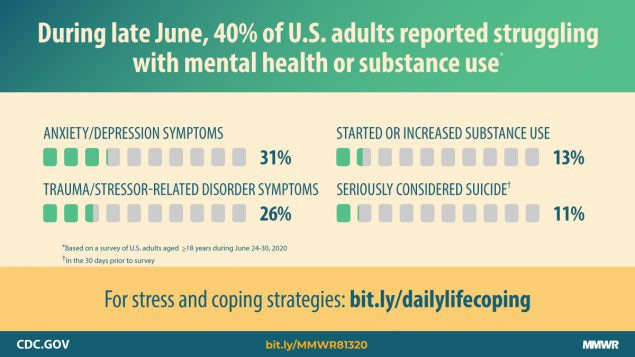

Zooming in, in June 2020, the Centers for Disease Control found that 40% of adults were experiencing mental health or substance misuse problems, and 25% of those 18-24 had thought about suicide. Individuals in minority groups have been particularly hard hit by this crisis, too – and their mental health was in jeopardy even before the pandemic began. Between 2007 and 2017, the suicide rate for Black youth nearly doubled from 2.55 to 4.82 suicides per 100,000. And Native American / Alaska Native youth, whose communities have been especially affected by the opioid and suicide epidemic partly due to intergenerational trauma, have the highest rate of major depressive episodes than any other racial and ethnic group.

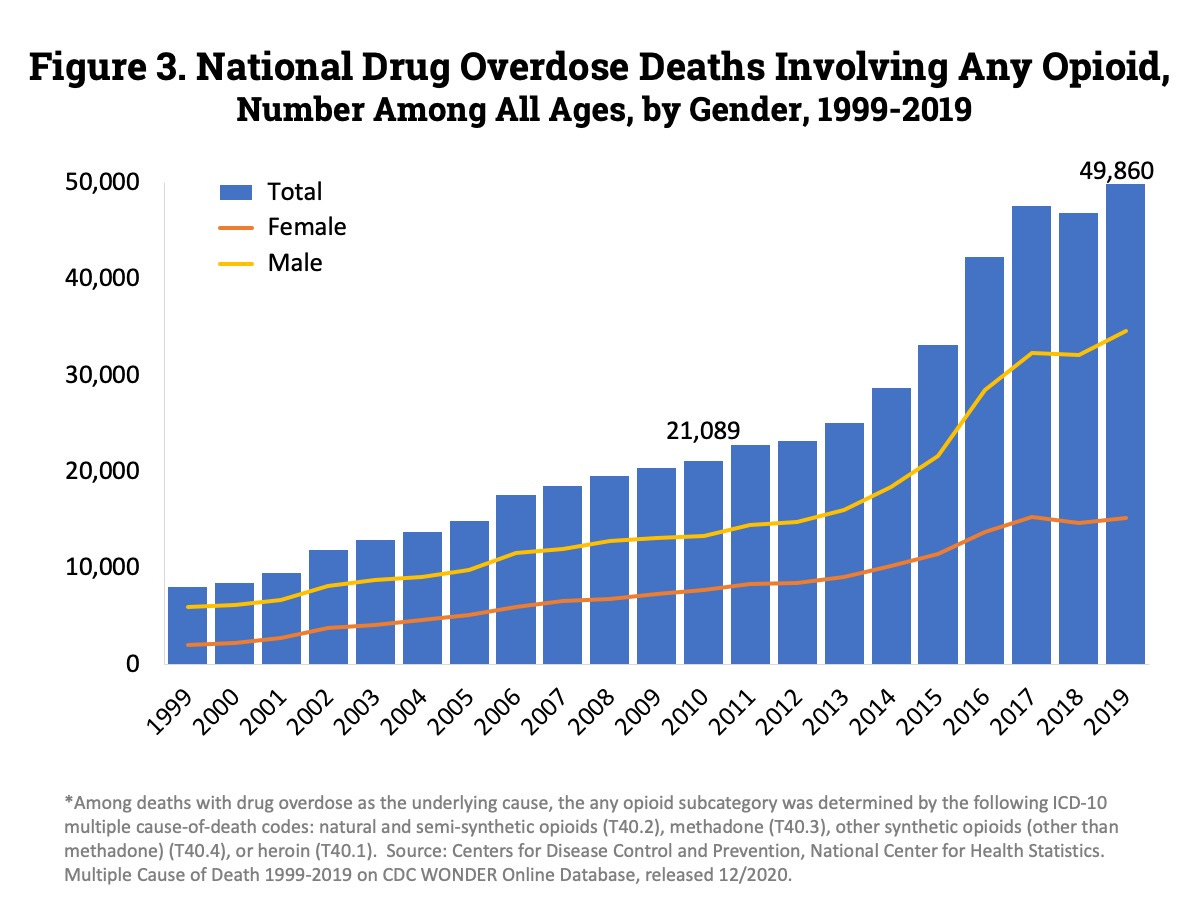

In addition, as this August 2020 Wall Street Journal piece by Noam Levey points out, even with presidential acknowledgement the ever growing overdose trends tied to our nation’s underlying addiction problem – specifically around opioids – is only getting worse.

We’re dying too soon, and basic policy issues of coverage and access - an issue that has been married to health insurance coverage as long as most of us can remember - remains elusive.

(I will return to this health insurance issue, specifically our problem enforcing mental health and addiction parity, in upcoming posts, but let me first set the scene.)

Studies show that cost and lack of insurance are barriers for people seeking mental health care, and even if a person has health insurance, it’s not always guaranteed that their mental health and/or addiction needs will be covered. One study from the actuarial firm Milliman, for example, found that people are often forced to turn to out-of-network providers six times more often for mental health and addiction care than for other types of medical care.)

Where access is concerned, ask yourself this question: What would I do and where would I go if myself or a loved one needed mental health care? Data indicates that for many, the answer is visiting the emergency department (ED): Over an eight-year span (2006-2014), our nation saw a 44% increase in ED visits involving mental health or substance use disorders, with more than one in eight visits related to mental health or substance misuse. ED visits involving suicide ideation went up 414% in the same time period.

This is problematic when you consider that EDs are a part of the health care system that is often ill equipped and unprepared to manage acute psychiatric crises. Oftentimes, they’re not the best places to be seen, but it’s the only place people think to go because some studies show the wait times for an outpatient appointment with a psychiatrist can last over a week to twenty five days to much longer. No wonder most people don’t get the care they need – 90% of people who need substance use treatment go without, as do 60% who need help with their mental health – until it’s nearly too late.

Even the most seasoned of mental health operatives before COVID-19 would initially struggle to come up with a different answer to those questions mentioned above. But we shouldn’t. We should know these answers and have a system that allows for seamless entry that is capable of helping us with whatever our problem might be.

THE OPPORTUNITY

The COVID-19 crisis has given us an unprecedented opportunity to examine mental health - what works and what doesn’t. We have learned that our health is impacted in ways that are not just about becoming sick with a virus. We have learned that our nation’s well-being includes factors like our mental health, our physical health, and our social and economic health, making clear that all of these should be forefront and integrated in our response and recovery plan if we hope to avoid going back to the way we were before – which, as I have outlined above, wasn’t working for most people.

I think we now have multiple opportunities to better address mental health. Here are just four:

Medicaid matters – strengthen it

Considering more than 77 million people are currently enrolled in Medicaid – the federally funded health insurance program for low-income Americans administered by their states – or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), focusing on bolstering mental health coverage via Medicaid is a great place to start. Oh, and don’t forget that Medicaid is the largest payer for mental health and addiction services in the country.

The evidence is clear that Medicaid expansion benefits beneficiaries mental health (and so much more). But despite this evidence, we still have 12 states who have not expanded Medicaid. Regardless of expansion status, there’s always something that can be done to improve our systems for mental health. Take for example a report that was released today by the National Association of Medicaid Directors entitled Medicaid Forward: Behavioral Health. This report is the first of a three-part series, and aims to inspire leaders at the federal and state level to reimagine what a true system of care for mental health might look like. And what a moment to reimagine. Leaders in our states are attempting to balance budgets and in daily contemplation of cutting or restructuring programs like Medicaid to do so - they might as well use that time to fix some of the structural problems that weren’t quite right in the first place.

This NAMD report offers several important options to strengthen how our states approach mental health – and to structure mental health and addiction in ways that are much more aligned with meeting the needs of the population. For example, Medicaid programs could begin to distance themselves from diagnostic or utilization criteria to determine if a person was eligible for a service. Requiring that an individual have a diagnosis before treatment can be authorized is an unneeded barrier for countless. Focusing more on functional criteria – things like social challenges – can go a long way helping a person receive care faster.

Rethink where care is delivered – integrate it

During COVID-19, telehealth services, especially for mental health boomed. Thanks to the disruption of traditional care delivery, restrictions on telehealth were lifted and more clinicians started using the service. And while telehealth is likely going to be here to stay, in and of itself, this service does not solve all our access woes.

“No wrong door,” a phrase that has been used before to communicate a commitment to streamlining care services so that a person can be identified and receive help wherever they present, remains an often elusive goal for mental health. It begins by bringing mental health and medical services together in a seamless and integrated way, and to create clear care pathways from the moment a person is identified as having a mental health need through their treatment and follow up. Right now, we often limit where a person can get care or set conditions that make it overly burdensome on the person and their family to find care.

We need to use this moment to examine our structures for mental health and begin to assess all the impediments that people will face – all the doors that are shut and keeping people from getting into care. This is not an easy exercise, but it’s the right one for leaders to embrace now by first asking themselves if there are any policies or programs that stand in the way of a person getting access to care wherever they present. Then, once those barriers are outlined, they will need to sum up the courage to design a new system and a new strategy for mental health.

The integration of mental health across clinical and community settings should be our calling card.

Create a full continuum of crisis services – build it

This past July, the Federal Communications Commission announced that by July 16, 2022, they would establish a three-digit phone number (988) that would connect callers to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (1-800-273-8255). This is much needed, but without resources to develop an infrastructure for our crisis response, we will just have yet another underfunded, overrun system that does not lead to change or worse gives people false hope that a solution is out there.

Ideally before the 988 hotline comes into effect, we will have an adequately funded infrastructure that creates clear pathways for people in various stages of crisis. Having mobile crisis teams that can respond to mental health crises like the CAHOOTS model is needed. However, not all counties, cities, and states will be able to use the same model (of note, there is the CAHOOTS Act being considered in Congress, which among other things would allow state Medicaid programs to pay for certain community-based mobile crisis interventions), and these local solutions need to be created so we do not default to a police response to a mental health crisis.

It is essential that we begin to think more about how to create an actual system for crisis response. Too many people fall through the cracks, end up being incarcerated, or in extreme cases, killed. 988 is a wonderful motivator for us to create the right type of infrastructure, and states are aggressively pursuing legislation to add more resources to support their crisis systems (e.g. per line, per month fees for 988 similar to 911).

Fix the financing – pay for it

Once we have a more integrated treatment and crisis response system in place, we need to make sure that financing issues – whether a person is on Medicare, Medicaid or a commercial insurance plan – don’t further hinder care. We must begin to move towards paying for value - for the things that matter to people - not just the fee for service widgets we have been trained to bill for (over and over). There are two issues with financing - how we pay for care and what we pay for. Both need to be reexamined.

What’s somewhat ironic is that now as we move towards more integrated financial models for mental health in places like primary care, we are being challenged to also address how to finance social determinants or community factors (e.g. housing, transportation) in the same settings. With the complex overlay of mental health with public health, health care, and community factors, now is the time to begin to test out ways to pay for these core functions in more global ways. The financing of mental health is overly complex yet we have learned too much about what doesn’t work to avoid addressing alterative models of financing that support integrated models of mental health care.

YOUR TURN

We have a true crisitunity in front of us.

Whether it’s a real word or not, it does accurately describe where we are right now. In the face of our most significant public health crisis, there does lie an opportunity to do something truly, officially, and finally meaningful for mental health.

We cannot squander this moment. Take action. Get connected to organizations who are working on this issue. Call your local elected official, let them know how your mental health has been impacted, and come prepared with solutions - and let’s pursue radical change together.

I couldn't agree more with all of the action points listed here. I worry, that in responding first to the physical health crisis component of COVID we limit the size of the funding pot needed to support the second wave of this pandemic, the larger, looming mental health crisis.